Bruce Russell

w.m.o/r 11 cd

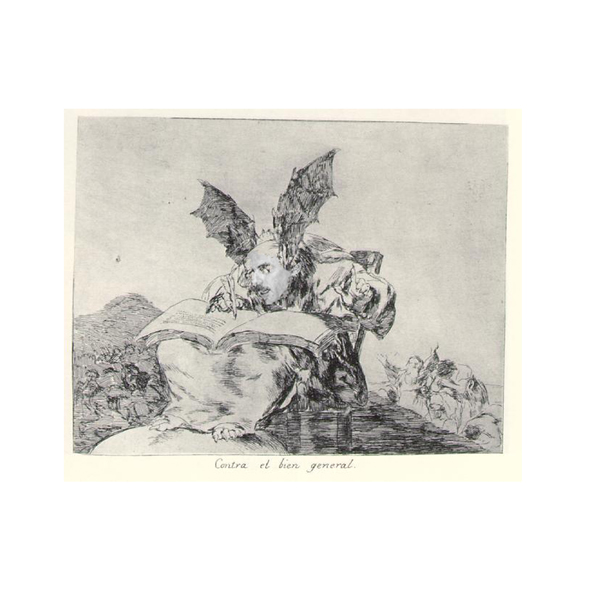

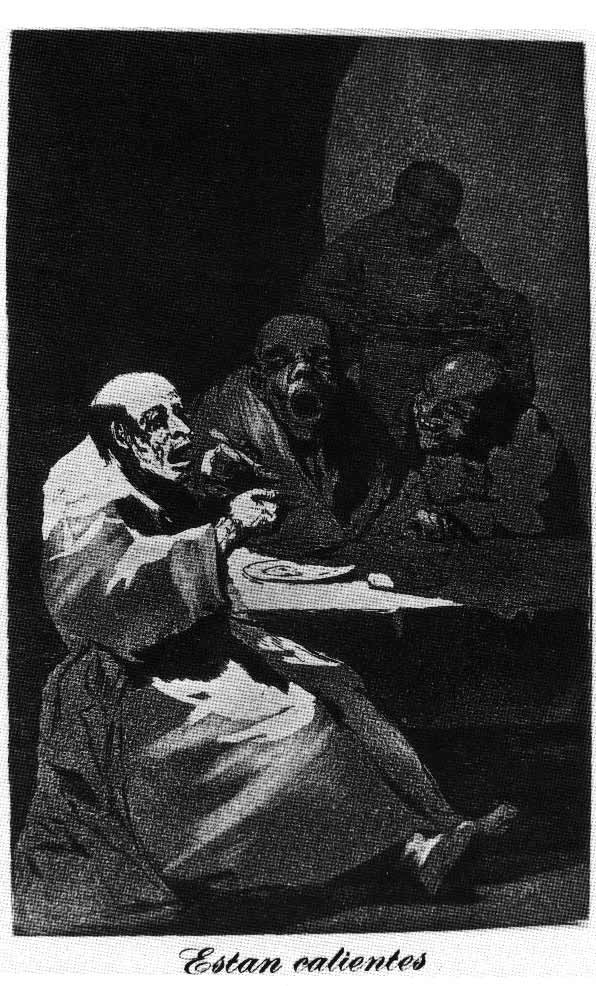

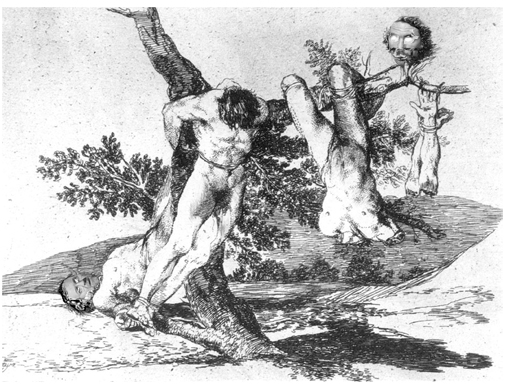

Los Desastres de las Guerras

Bruce Russell ~ electric guitar i-iv

Mattin ~ computer feedback iv

Yo

le pregunté a la Muerte [I asked Death a question]

~ 6’ 39”

El sollozo de las almas perdidas se escapa por su boca redonda [The

sobbing of lost souls escapes through its round mouth]

~ 3’ 19”

En la redonda encrucijada, seis doncellas bailan… [In the round

crossroads, six maidens are dancing…]

~ 17’ 55”

iv. Los Desastres de las Guerras [Disasters of War] ~ 30’ 07”

i-iii ~ mono

analogue tape recordings made at the Temple of Music

13 March 2004, engineered Bruce Russell

iv ~ stereo DAT recording by Mattin, made at a performance at The

Physics Room, Christchurch 26 February 2004.

Text:

Bruce Russell -Practical Materialism Lesson three

Matthew Hyalnd -Disasters of Peace

Mattin -Refleciones en Identidad

Practical Materialism: Lesson Three

Concerning the Duende

duende / n. 1 an evil spirit. 2 inspiration. [Sp.]

“All that has dark sounds has duende.”

F.G. Lorca: ‘Theory and Function of the Duende’, in Selected Poems:

Penguin Books; 1960,

p. 127

As the Spanish Instrument par excellence, the guitar comes pre-loaded

with a burden of extra-musical cultural significance. When we play the

guitar, we are always playing with a caravan of images which trail us

like ghosts across a television screen. Jimi Hendrix; Robert Johnson;

and a crowd of anonymous Spanish gypsies, swarming like penitents on

the road to Santiago.

The spirit of the guitar is the duende, neither angel nor muse, but

animating spirit, equally malevolent and indifferent, demanding nothing

but blood on the strings.

“Spain is always moved by the duende… being a nation open to death.”

Lorca, p. 136.

For me as an artist, sound is the central activity - which in my case

is the attempt to say something from the self itself. Opening the self

to allow this expression to emerge is a problematic exercise. The best

results come from a loss of conscious control over this process, an

opening to ‘something other’. In the Spanish model, this is the duende

speaking. Being an evil genius, the art inspired by the duende is never

simple; clear; or light-filled. It is dark; ambiguous; and tinged with

horror - the horror of our contingent existence. This is why an appeal

to the duende is always a looking-within, this is where the abyss opens.

‘Diving in’ is the metaphor of improvisation. A recital of compositions

cannot be a real encounter with the duende, only when we put ourselves

on the line is the duende awakened.

“The appearance of the duende always presupposes a radical change of

all forms based on old structures”

Lorca, p. 131.

For me the guitar has endless possibilities, especially once the twin

tyrannies of the song and of conventional technique are overturned. In

this way the realm of practical freedom is briefly created, within the

alienated form of artistic expression. Lacking easy access to the

euphoria of the revolutionary moment - Paris 1870; Petersburg 1917;

Barcelona 1936 – the option of creating a personal space for revolution

on stage is more readily achievable as a laboratory for the duende.

Using the guitar purely as a noisemaker has the effect of ‘gutting’ the

troubadour archetype, ‘the gypsy with the guitar’. The ‘bits’ of the

archetype are still there, ‘the rebel’ (actor), ‘the guitar’

(signifying object), ‘the stage’ (context) but put together in the

wrong order. The dislocation experienced by the audience [‘what is this

noise?’] is the crack through which the duende can enter a public

space, like a matador entering the bull ring, banderillas in hand - a

las cinco de la tarde.

The guitar as loaded cultural signifier is vital to this process, its

abuse is the jemmy-bar that opens the window of opportunity to admit

the unwelcome shock of the new. Everyone understands what the guitar

‘means’ in the context of a performance. Inverting this is a potent

signifier of cultural dislocation.

Practical freedom presupposes an outlook of practical materialism; an

engagement of autonomous subjects with real objects within a social

context. The duende is a metaphor for creativity in just such a

setting. It elevates human subjectivity to a higher plane of existence,

an all or nothing throw of the dice, balls on the line man, ‘do you

take a chance, fan?’.

“The real struggle is with the duende… to help us seek [it] there is

neither map nor discipline.”

Lorca, p. 129.

Having ‘made’, or ‘had made for one’ the choice of the electric guitar

over other potential contenders in instrumentation, certain parameters

are set.

Technical limitations in terms of guitar playing can be a positive

advantage in the creation of a genuinely ‘alternative’ vocabulary for

the electric guitar. To be technically limited in the traditional

sense, can be combined with developing aptitude at an extended and

idiosyncratic form of technique, that is predicated on rather different

strategies from those of most players. If one works with the guitar as

a signal generator, and as a noise-maker in the acoustic sense, there

is much that can be achieved with a complete ignorance of musical

theory, notation and conventional aesthetics. I myself am not much

interested in the specific frequencies and harmonics of the sound, or

even making them predictable or explicable. My interest is in textures

of noise, and juxtapositions that are often outside the vocabulary of

‘real music’.

For me the performance is in a real sense a wrestling bout with an

implacable foe. The duende resides in the guitar, in the electrical

circuitry, in the exigencies of the performance itself. All these

variables can conspire to seek to overcome me. How, or if, I emerge

unbloodied is the drama of every performance, with or without an

audience at hand.

There is no practicing with the duende, every encounter may be le

dernier combat.

“The duende can never repeat itself.”

Lorca, p. 137.

The main thing is to keep surprising oneself, as well as the audience,

in that way every performance involves giving the utmost to the

audience, or nothing at all.

For me the guitar is a totem; my efforts with the guitar underpin every

piece of sound praxis I attempt in an artistic sense. I have the

courage to experiment with other things, when I have the urge to do so,

because I am anchored in my relation to the guitar. The real trick is

to express something inherent to myself, and uniquely of myself, in

this more or less arbitrarily chosen activity. It would be inauthentic

to deliberately choose an artform at which I was naturally gifted. That

would be too easy. The duende does not emerge from ease and

familiarity, but from danger and uncertainty.

The real attraction of the guitar for me (as instrument qua instrument,

apart from the cultural baggage alluded to earlier) is that it is a

resonating object. With a keyboard or a sampler, you just push buttons;

with a guitar you have wood, metal, strings, wires and pickups. If you

hit a string hard, it sounds different than when you hit it softly. If

you hit it with an object, it sounds different again. If you smack the

body of the guitar with a hammer while moving a five-pound flat-iron up

the strings, it sounds different again, both at the instant you hit it,

and for quite some time thereafter, in a dialectic of truly

electro-acoustic attack and decay. Further, the pickup is a microphone

that generates an electric signal, that too can be the subject of

‘interventions’. It changes depending on the signal path (effects) and

relationship to the speaker (feedback).

All guitars are very sensuous instruments, any movement can set them

going. Merely tuning the strings in sympathy can be enough to activate

a sound-torrent of positively Dionysian proportions. ‘Sensuous’ in this

sense means ‘responding to physical stimuli’, and ‘existing within the

realm of the physical’. The opportunities to intervene with the

electric guitar are very many, if the player approaches the business

with the correct attitude, and in willingness to admit the influence of

the dark spirit over the form the activity will take.

“It is clear that each art has a duende of a different kind and form,

but they all join their roots at a point where the ‘dark sounds’ of

Manuel Torres emerge, ultimate matter, uncontrollable and quivering

common foundation of wood, of sound, of canvas, and of words.”

Lorca, p. 139.

The potential limitation is not in the instrument, but in the

instrumentalist, and his or her willingness to be situated in the realm

of practical freedom.

When the duende comes to the door of the bar “…dragging her wings of

rusty knives along the ground” [Lorca, p. 132.], there is only one way

to respond to the apparition - we play.

Bruce Russell

Lyttelton, NZ

April 2004

Disasters

of Peace

You love life, we love death

(from Associated Press translation of videotaped statement in the name

of 'Al-Qaeda', claiming authorship of the March 11 Madrid bombings.)

These words were seized on enthusiastically in

Europe and America by Authorities (in both the active and the

contemplative senses: 'leaders' and 'experts') who sought in the Atocha

wreckage proof of the stubborn, atavistic anti-rationality of the

Islamic mind. But this 'example of what the Prophet Mohammed

said' can also be understood in almost exactly the reverse sense.

Not as pre-modern cruelty howling theatrically against humanist values,

but as an in'humanly' rational description of bio-thanatopolitical

reality in the contemporary material world.

(Any objection based on what's already known about the

'we' of the statement would barely merit a dismissive gesture

here. But in order to pre-empt all confusion, some obvious

principles may need to be spelled out once more. First, nothing

whatsoever is known about the speaker's relation to the ephemeral

subject 'Al-Qaeda', or about that subject's relation to the

bombings. And even if speaker, bomber and 'Al-Qaeda' are presumed

to be identical, the latter's (presumed) diffuse organizational form

and its still more nebulous political constituency mean that who is and

is not of the 'death-loving' party is a matter of idle

speculation. But more importantly, the statement matters not for

what it reveals about the speaker, but for its independent sense: for

what it can be made to say about the world. As in the

interpretation of any other text, there is no reason automatically to

identify 'I' (or in this case, 'we') with the (presumed) author.

Coherence, not biographical information, is what authorizes any

reading.)

Some speakers using the 'Al-Qaeda' brand have

claimed to be acting in the name of the Iraqi and Palestinian

populations. The question of such unsolicited political

representation's 'legitimacy' is meaningless, of course, where the

questioner's approval is not being sought. Engaged intellectuals

from neocon think tanks to liberal Muslim columnists have already

squandered enough billions of words (or tonnes of 'general intellect')

on 'critiques' of an absolute non-interlocutor. But because the

concentrations of besieged life in Iraq and Palestine are also

saturated with the televisual gaze, in spectacular perception they

symbolize all the life capable of occupying the 'we' position in the

'Al-Qaeda' statement: the global 'class with nothing to lose and

therefore nothing to defend'[1.] in the most literal, urgent

sense.

On these terms, the rationally inhuman paraphrase of 'you

love life, we love death' would run:

Exposure to death (our own and that of others) occupies our

lived time (and living memory, and foreseeable future), so fully that

the distinction between 'life' and 'death' breaks down. Unlike

you, we have no life separate from death to lose or defend: thus it

only remains to become death-levellers, to redistribute our great

surplus of death so it engulfs and becomes indistinct from your life.

The condition of this statement's truth is the

self-evident fact that in this world, as it is now, the distribution of

forced exposure to death (or the problem of survival) is violently

unequal. This is no more a matter of natural tragedy or immoral actions

than it is of divine visitation. To put it with appropriate

crudeness, the present distribution of death reflects the division of

labour in a world where capitalism is universally indifferent to the

distinction between labour-power's 'life' and 'death', as long as its

living and dying yields value. Dying is work when life is wholly

consumed in producing value. A perfectly 'normal' phenomenon,

inasmuch as millions of lifetimes are filled by waged and unwaged

labour that eventually breaks or exhausts them. An 'extreme' case

like the war and ensuing primitive accumulation in Iraq only

demonstrates the same thing: by living and dying under multilateral

siege, the newly proletarianized population produces the conditions for

the security and reconstruction businesses, literally paying for the

contractors' profits. The same logic underlies the

transformation, noted by the SPK/PF(H), of 'biomatter man' – cells,

genes, organs – into a productive, i.e. labouring, force. The

universal equivalent transcends the life/death threshold: 'everyone is

totally valuable, dead or alive'[2.].

Capital's formal obliviousness to the difference between

death and life almost seems to be parodied by the attitude of the class

for whom existing social relations have provided plenty to lose and

defend. Continuous experience of shelter eventually breeds

forgetfulness of the shelter itself, and of the reality of what it

shelters from. This forgetting of death sometimes takes the form

of an anomalous ignorance among 'educated' subjects, explicable only in

terms of an inability to conceptualize and remember in the absence of

direct exposure. Thus an editorialist in Italian left-moralist

daily L'Unità ('founded by Antonio Gramsci', etc), cancelled 60

infernal years to call the Madrid bombs 'the worst barbarity in Europe

since Nazi Germany'.

Affluent societies' officially-sponsored obsession with

'risk' and its management also depends on ignorance of death, or deep

assurance of ultimate preservation. The tendency for the absence

of any perceptible threat to appear primarily as sign of the threat's

potential presence (as in 'anti-terrorism' vigilance) demands that the

apparatus of 'security' fill every space indifferently. This wish

bespeaks an enormous, ingenuous confidence in that apparatus, endowing

it with the capacity to measure and pre-emptively control a risk as

infinite as uncertainty itself [3.].

But the fact that so many life-lovers enjoy a subjective

experience of shelter does not make their sense of security a true

one. What they are really forgetful of is that capital's

indifference to 'life' and 'death', which their own insouciance mimics

playfully and which has left them living-space to play in, also

guarantees that they themselves are never safe. The law of value

is as unconcerned with their life as with others' death: the

non-sensation of non-exposure is a contingent privilege, liable to be

revoked devastatingly, sunk into in the most abject 'bare life', at the

remotest shift in global class cold-war. But one of the

'blessings' of their once-removed exposure, their brittle shelter, is

forgetting that such special status is unusual and revocable. It

remains to be seen whether another violent announcement that all

privileges are cancelled, made 'on behalf of' the unsheltered, will

disturb the oblivious, laying bare the minimum they hold in common with

death-lovers: not 'humanity' but exposure, eligibility to be consumed

by the apparatus that so far happens to have spared

them.

[1.] See Amadeo Bordiga, 'Fundamental Theses of the Party':

http://www.marxists.org/archive/bordiga/works/1951/fundamental-theses.htm

[2.] SPK.PF(H), 'The Communist manifesto for the Third Millennium':

http://www.spkpfh.de/GENOZIDengl.html

[3.] In this way the risk-management congregation attributes to

preventive mechanisms precisely the same spurious capacity for

metacalculation claimed by the systems of professional gambling.

See 'Say Fear is a Man's Best Friend', Datacide 9 & metamute:

http://www.metamute.com/look/article.tpl?IdLanguage=1&IdPublication=1&NrIssue=24&NrSection=5&N

LAS

MULTITUDES SON UN ESTORBO 1

A finales de abril Tony Negri vino a Madrid y habló con mucho

entusiasmo del 13 M como "La Comuna de Madrid", un claro ejemplo del

concepto de "multitud" en acción, conjunto de singularidades que

se reunen en un momento decisivo sin tener que atenerse a ninguna

sigla, partido o identidad concreta. Esta multitud demuestra que

fácilmente puede ser recuperada para ciertos fines (en el caso

del 13 M como una estrategia politica empujada fuertemente desde el

grupo PRISA hacia la dirección de un partido: PSOE), o en el

caso aún mas patético de las manifestaciones contra la

Guerra de Irak, sí que hubo muchisima gente y tal vez muchisimas

ideas pero con la imaginación insuficiente para demostrarlas

fuera de manifestaciones convencionales. Todos sabemos que estas

manifestaciones no fueron muy lejos. La ambivalencia de la multitud,

tan peligrosa como poderosa, puede llevarnos a momentos de intensa

resistencia y al conformismo más reaccionario. Por su

naturaleza, la multitud encuentra dificultades pera crear constancia ,

tambien esto va en contra de su manera de ser ya que bajo esta

constancia se estaria definiendo una identidad. Como ya hemos comentado

la potencia de la multitud puede ser facilmente recuperada y utilizada

para servir a ciertos intereses: bien encajar dentro de estrategias

politicas o en conceptos teóricos de moda. Por tratar de dar la

maxima visibilidad a sus acciones, la multitud puede llegar a perder el

control sobre su propia representatibidad. Pero aqui estamos jugando al

juego de los medios de comunicación, en el cual de nuevo la

constancia pierde cualquier tipo de efecto.

La multitud, siendo utilizada por otros, gana una identidad no deseada;

y es aqui donde reside el problema, en la incapacidad de esta multitud

para responsabilizarse de sus actos, para coger las riendas de sus

acciones. El concepto de multitud va dejando paso a otro más

constante con el cual mucha gente hoy en día se puede sentir

identificada, que es el de precario. Si la ambivalencia de la multitud

estaba menos definida y es más fluctuante, la ambivalencia del

precario es su condición de vida. Un momento estamos trabajando

y al siguiente tratando de romper esa cadena de trabajo. Esto no puede

llevarte más que a pensar de una manera esquizofrénica, a

sabiendas de que por mucho que estes resistiendo hoy, no olvidas que en

un dia, un mes, o un año volverás a estar trabajando.

¿Cómo puede uno expresar su singularidad de la manera mas

singular y a la vez estar en comunicación con otros?

Paolo Virno en el libro “Gramática de la multitud” comenta

cómo el lenguaje se ha convertido en eje central del trabajo, en

herramienta de trabajo. "En los procesos de trabajo

contemporáneos, hay constelaciones enteras de conceptos que

funcionan por si mismas como "máquinas" productivas, sin

necesidad de un cuerpo mecánico, ni siquiera de una

pequeña alma electrónica. Es un error comprender tan

sólo o sobre todo la intelectualidad de masas como un conjunto

de funciones: informáticos, investigadores, empleados de la

industria cultural, etc. Mediante esta expresión designabamos

más bien una cualidad y un signo distintivo de toda la fuerza de

trabajo social de la época postfordista, es decir la

época en la que la información, la comunicación

juegan un papel esencial en cada repliegue del proceso de

producción; en pocas palabras en la época en la que se ha

puesto a trabajar al lenguaje mismo, en la que éste se ha vuelto

trabajo asalariado - tanto que "libertad de lenguaje" significa hoy ni

más ni menos que abolición del trabajo asalariado".

Entonces, ¿cómo podemos encontrar “la libertad del

lenguaje”?

La música improvisada es una busqueda de esta libertad ya que

constantemente se mueve alrededor de un lenguaje que no se puede

establecer, solidificar ni institucionalizar. Su naturaleza

efímera y a la vez necesitada de otros ( para tocar y como

publico) incorpora nociones políticas.

“Las artes que no realizan ninguna <<obra>> tienen una gran

afinidad con la política. Los artistas que las practican

–bailarines, actores, músicos– necesitan de un público al

que mostrar su virtuosismo, así como los hombres que

actúan [politicamente] tienen necesidad de un espacio con

estructura pública; y en ambos casos, la ejecución

depende de la presencia de los otros.”2

Es por esto que es necesario encontrar nuevas formas de lenguaje, en el

caso de la música improvisada, experimentar con tu instrumento y

llegar a zonas donde estipuladas previamente ciertas reglas,

éstas se rompen dando paso a la convulsión de tus deseos.

Es importante profundizar abriendo nuevas grietas en las maneras

convencionales de tocar, encontrando nuevos aliados en esa busqueda,

así, la música improvisada es capaz de abrir

posibilidades para llegar a comunicaciones donde no se trata de

alcanzar acuerdos o acabar canciones sino de destripar las marginadas

condiciones materiales del instrumento.

Marginadas y esterilizadas por fabricantes de instrumentos y

músicos que no centran su actividad en dar rienda suelta a sus

deseos sino en cumplir una funcionalidad en la cadena de montaje de la

industria cultural.

En la improvisación es el deseo el que mueve a los individuos,

que de primeras ya se saltan las reglas como bien explica Bruce en su

texto. Estos deseos no son inculcados por estructuras del conocimiento,

en otras palabras, por estructuras de poder previamente concebidas sino

que se dejan atrás para sacar partido a los intereses

particulares de cada individuo. Estos intereses no son más que

la intesificación de cada momento a la la hora de interactuar

con tu instrumento, músicos , público y espacio.

El que en cada momento todo esté en juego y no haya miedo de

defender o salvaguardar secretos o trucos. Compartir toda tu

creatividad ininterrupidamente.

1 Eskorbuto

2 Hannah Arendt “Entre el pasado y el futuro. Seis ejercicios de

pensamiento politico”. P.206.

Mattin

Bilbao, Julio 2004

Reviews:

Best

record of the year 2004 for Brian Morton (The Wire, Issue 251

Jan.2005)

The Wire (UK) and Paris Transatlantic (France)

Bruce Russell's Los Desastres De Las Guerras, an album haunted by the duende of Federico Garcia Lorca's "Theory and Function of the Duende", a text from which guitarist Russell extracts several quotations to illustrate his own essay "Practical Materialism: Lesson Three". This is one of three tracts accompanying this release, the others being Matthew Hyland's "Disasters of Peace", a Marxist analysis of Al Qaida's claiming authorship of the Madrid bombings on March 11th this year, and Mattin's own musings on the mass protests that took place in the Spanish capital two days later. That same day, Russell recorded the three magnificent and desolately throbbing guitar improvisations that open the album, Lorca poems once more providing their titles. The danger implicit in the concept of duende - the noun is untranslatable, combining the notions of evil spirit and inspiration - has long been a central element of Russell's work both as a solo performer and with The Dead C. "The duende resides in the guitar, in the electrical circuitry, in the exigencies of the performance itself. All these variables can conspire to seek to overcome me. [T]he performance is in a real sense a wrestling bout with an implacable foe." As foes go, there are few more implacable than Mattin himself, unleashing a torrent of terrifying feedback from behind his computer without batting an eyelid. On the album's title track, a thirty-minute duo recorded in Christchurch's Physics Room, Russell's mournful strums are suffocated by clouds of howling feedback in a slow-building electrical storm of hums and buzzes that might have a made a fitting epitaph to the bombings had it not been recorded a fortnight before they occurred. To quote Russell once more: "When the duende comes to the door of the bar 'dragging her wings of rusty knives along the ground' (Lorca), there is only one way to respond to the apparition - we play." She was there all right on February 26th.—Dan Warburton

Revue & Corrigée (France)

Nouvel opus solo

de Bruce RUSSELL " Los Desastres de Las Guerras " est sans aucun doute

son album le plus fascinant, le plus beau, celui qui tourne autour de

quelques accords approximatifs et pourtant sublimes, dans la

répétition et le trébuchement, attiré comme

par un aimant par ces notes ferreuses et les résonances magiques

des cordes ; ritournelles métalliques minimalistes comme le

blues pouvait en faire. Ce disque est un album authentique de blues,

pas un de ces hommages obscènes à Robert Johnson

façon Eric Clapton et tiroir caisse, mais son esprit entre

aperçu et depuis avec çà au fond de l’être.

" For me a guitar is a totem ", dixit Bruce RUSSELL, nul doute que sa

pratique relève du vaudou, ranimant les esprits morts du blues

dans la performance et l’électricité qui s’y consume. Il

trouven, plus qu’il ne cherche, des techniques obliques sur son

instrument, étendant son vocabulaire à ce que les

lecteurs de " guitar players " d’ordinaire éliminent. " The

potential limitation is not in the instrument, but in the

instrumentalist, and his or her willingness to be situated in the realm

of practical freedom ". Le dernier morceau qui donne son titre à

l’album est un duo avec le jeune musicien basque Mattin à

l’ordinateur. Radicalement dans les matières, façon

sculptures de Richard Serra, ces vastes structures de métal qui

redécoupent l’espace ou plus encore les barricades libertaires

de 68 quand la vie s’inventait à travers la vérité

du désir. Et le nôtre ici c’est ce son qui le porte.

Michel HENRITZI

VITAL WEEKLY (Netherlands)

Maybe I didn't write this very often before, but I think Bruce

Russell is one of the more interesting improvising musicians there

is. Although he is far away in New Zealand, we don't see him very

often around in Europe or America and therefore he is not very often

part of the improvisational music circus mentioned before. On his CD

there are four pieces, all dealing with the disasters of war. Three

of them are Bruce solo on his electric guitar and one is a duet he

recorded with Mattin in live concert in New Zealand. For his three

solo pieces, Russell plays electric guitar through some echo unit,

carefully playing around with silence and noise in a very thoughtfull

way. In the duet, Russell extends his guitar playing and serves the

computerized feedback of Mattin who takes in return the room

vibrations to let things explode. This is a very nice release, not

just the music, but also the philosophical texts that are also

enclosed, and which are certainly not easy to understand.(FdW)

GIAG (a.k.a. Gaze Into A Gloom)

- electronic music & non-music website. (Latvia)

Experimental

music as a term has without doubt been used in so many different

occasions that it would really be impossible to clearly define what it

actually is about. Bruse Russell approaches his blend of experimental

sounds from a rather minimalistic angle, nonetheless constantly

exposing some harsher and unexpected elements beneath it all. Russell's

works remain quite solid, thus giving it a more ambient sense.

Merje Lõhmus (a.k.a. Mad Sister), 2004

Брюс Расселл – гітарист-дилетант, що має за плечима більш ніж двадцятирічну кар’єру в новозеландському нойз-(рок)-андеграунді. Зокрема, він – учасник відомого в нойзових колах гурту Dead C, а також – засновник кількох незалежних лейблів. Альбом “Воєнні нещастя” випущений на лейблі Маттіна w.m.o/r і містить чотири імпровізаційні треки. Перші три – це Расселл наодинці зі своєю електрогітарою, студійний запис. Четвертий, титульний – це гітара Расселла плюс комп’ютерний фідбек Маттіна, запис спільного виступу, який відбувся в лютому 2004 року.

Життя

в ритмі заїкання – так хочеться назвати

перший трек альбому. Це щось, схоже на

рок – може, навіть на пост-панк – але

пульс музики задає не ритм-секція

басу-й-барабанів, а ритмічне заїкання

delay-примочки, через яку пропущений звук

гітари. Расселл зминає (заглушені

чавканням примочки) гітарні акорди в

риф, розминає той риф у руках, мов глину;

відмічає цими довільними акордами та

паузами ритмічні акценти (гітара

акомпанує власному чавканню та заїканню).

Деколи ненароком гітарист шарпає струну

сильніше, і гітара крякає, як якась

домашня птаха – різкий звук пробивається

крізь загальну заглушеність і таким

чином задає ще один, третій рівень

ритмічного акцентування. В цілому в

Расселла виходить щось на кшталт

старомодного, ручного глітчу.

...Описуючи свою практику приборкування електрогітари, в буклеті, який постачається разом з диском, Брюс Расселл говорить про duende (демон натхнення іспанських фламенко-гітаристів), цитуючи Гарсія Лорку. Десь між капризним електро-duende та напіврозсіяною лабораторністю і коливається ця музика. Другий трек – трьохвилинна мініатюра в квазі-Дерек-Бейлівському стилі (з сильним наголосом на “квазі”). Досить рухливо, і досить гарно. Третій трек – штудія пасивної монотонності. Низьке зудіння, тихі мікрохлопки та мікропостріли; пульсація зудіння часами розсмоктується в статичність, робиться то тихіше, то настирніше; часами музика одним краєм занурюється в фідбек, який починає пульсувати синхронно з зудом, змагаючись із ним в занудності.

Четверта імпровізація – півгодинний дует з Маттіном – виразно контрастує з соло-імпровізаціями Расселла. Присмак рутинності кудись вивітрюється. З малопоетичного й засміченого (шипінням підсилювачів, розмовами публіки та іншими не дуже виразними шумами) ґрунту перших хвилин, ніби ненароком, вагаючись, виростає і розквітає складна імпровізаційно-імпресіоністична поема – якщо тільки можна застосовувати слова “розквіт” та “імпресіонізм” по відношенню до цієї гри грубих стиків, пробоїн і дефектів. Але якщо вже продовжувати паралель із симфонічною поемою, то в ролі симфонічного оркестру тут виступають терзані болячками нестабільні частини інструментів, неналаштована підручна апаратура, шнури, роз’єми... а руки музикантів зі змінним успіхом намагаються, наче з великої відстані, диригувати усім цим недоприрученим причандаллям: збурюючи зворотні зв’язки, зіштовхуючи їх з то з гітарними пульсаціями, то зі спотвореними гітарними акордами, різко втихомирюючи їх висмикуванням шнурів. У цьому іржаво-рваному калейдоскопі настроїв є чимало справді пафосних спадів і зрушень... посеред звалища звукового сміття ніби на одну мить матеріалізується у вигляді землетрусу якийсь пафосний дух-полтергейст: може, це – дух Гектора Берліоза? дух Стравінського? duende? (а може, це мені тільки так здається?)... Так чи інакше, тут вчувається активна присутність руйнівних – а може, навпаки, рушійних? – сил, що ніяк не дають грубому інструментарію (електрогітарі й комп’ютеру) та його обслуговуючому персоналу (музикантам) працювати “спокійно” – себто, котитись за інерцією.

Андрій Орел